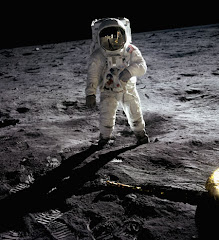

"In my view, the emotional moment was the landing. That was human contact with the moon, the landing…. It was at the time when we landed that we were there, we were in the lunar environment, the lunar gravity." - Neil Armstrong

Neil Armstrong's words to me, in a 1988 interview, came as a real surprise. Like most people, I think, I had expected that for Armstrong, the moment when he took humanity's first step onto another world would have been the ultimate high point of his Apollo 11 mission. As one of the 600 million people who witnessed history's first moon walk on live TV and radio, I remembered my own sense of awe seeing Armstrong's "one giant leap for mankind."

Of all the challenges Armstrong and his crew faced on Apollo 11, the landing itself was far and away the most difficult. Even if there were no malfunctions or other technical problems—an unlikely scenario—the descent would test the abilities of the entire Apollo team, Mission Control, as much as the astronauts themselves. In just 12 minutes, Armstrong and co-pilot Buzz Aldrin had to bring their lunar module Eagle from a height of 50,000 feet, orbiting at a speed of several thousand miles per hour, down to the surface in what amounted to a controlled fall. With no atmosphere, neither wings nor parachutes would have been useful; the only means of controlling the descent was by varying the thrust of Eagle's descent rocket. Adjusting the lander's flight path was especially tricky; with the craft balanced on rocket thrust, changing direction required tilting the entire spacecraft slightly to one side. And as Armstrong and Aldrin were all too aware, there was only enough fuel for one landing attempt.

And they almost didn't pull it off. The problems began soon after Armstrong and Aldrin began their descent on July 20, 1969. First it was trouble with communications with Earth. Then, alarm tones in the astronauts' headphones signaled something even more serious: the onboard computer, which was controlling the craft's speed and orientation, was becoming overloaded with tasks. . .

By Andrew Chaikin 7-17-09 Scientific American

http://tinyurl.com/lm97ew

10 years ago

No comments:

Post a Comment